Africa is losing the plant diversity that underpins food security, nutrition, climate resilience and livelihoods across the continent.

This is according to the Third Report on the State of the World’s Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture, which was published by Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) after its launch in Nairobi, Kenya.

The report’s findings show that crops along with their varieties and wild relatives, as well as other wild plants harvested for food, are disappearing faster than they are being conserved. These resources are essential for helping agrifood systems the way food is produced, processed and consumed, adapt to climate change, which is increasingly felt through erratic and extreme weather.

“This report shows clearly that Africa is losing plant genetic diversity at a pace that threatens food security, nutrition and the overall resilience of agrifood systems,” said Chikelu Mba, Deputy Director of FAO’s Plant Production and Protection Division.

“Crop diversity including farmers’ varieties or landraces, wild food plants and the genetic relatives of major crops is essential for developing progressively improved crop varieties needed to climate-proof the continent’s agrifood systems. Yet many of these resources are disappearing faster than they are being protected, meaning their inherent potential may never be fully realised not for the current generation, and certainly not for those who come after us,” he added.

Locally adapted crop varieties developed and passed down by farmers over generations scientifically known as landraces are disappearing from farms across Africa. These include varieties of staple crops such as sorghum, millet, yam, rice and traditional cotton. Such crops are often better suited to local soils and climates than commercial varieties, some of which were not bred for Africa’s diverse agroecological conditions or farmers’ preferences.

In Sub-Saharan Africa, about 16 percent of more than 12,000 distinct locally adapted crop varieties recorded across 19 countries were found to be threatened, narrowing farmers’ options as droughts and heat intensify.

“Africa’s food security and nutrition depend on the widest possible diversity of crops, trees and wild plants that farmers and communities have relied on for generations. As climate change accelerates, losing this diversity means losing the very options that allow agriculture to adapt,” said Éliane Ubalijoro, Chief Executive Officer of the Center for International Forestry Research and World Agroforestry (CIFOR-ICRAF).

The report also highlights sharp declines in wild food plants, which provide essential nutrients and act as safety nets for vulnerable populations during times of food scarcity. These include baobab, shea, marula, tamarind and African bush mango. Indigenous leafy vegetables commonly eaten across the continent including amaranth, spider plant, African nightshade, cowpea leaves and jute mallow are facing similar pressures.

More than 70 percent of assessed wild food plant diversity in Africa is threatened, mainly due to habitat loss, land-use change and climate stress, a rate of decline double the global average.

The report further draws attention to the loss of crop wild relatives, wild plants related to major food crops such as sorghum, millet, rice, yam, cowpea and African eggplant. These plants carry traits for drought tolerance and pest and disease resistance that are essential for future crop improvement. Over 70 percent of assessed crop wild relatives in Africa are under threat, while African genebanks conserve only about 14 percent of those collected, placing many adaptive traits at risk of irreversible loss.

“Plant genetic resources are the foundation of sustainable agrifood systems. Without stronger policies, investment and coordination, Africa risks losing irreplaceable plant diversity that supports livelihoods, food security and nutrition, and the ability of farming systems to withstand climate shocks,” Mba said.

Extreme weather events linked to climate change are accelerating these losses. Drought now drives nearly two-thirds of emergency seed interventions across Africa, with 110 responses recorded in 20 countries. While such interventions help farmers restart production, repeated emergencies place heavy strain on local seed systems and can displace locally adapted crop varieties with those poorly suited to local conditions.

The report also raises concerns about the security of Africa’s seed collections. Around 220,000 seed samples from nearly 4,000 plant species are conserved in 56 African genebanks, yet only about 10 percent of collections are safely duplicated elsewhere, leaving them vulnerable to conflict, flooding, power failures and chronic underinvestment.

“Conserving and using Africa’s plant genetic resources is not a luxury,” Ubalijoro said. “It is a necessity for resilient agrifood systems in a changing climate.”

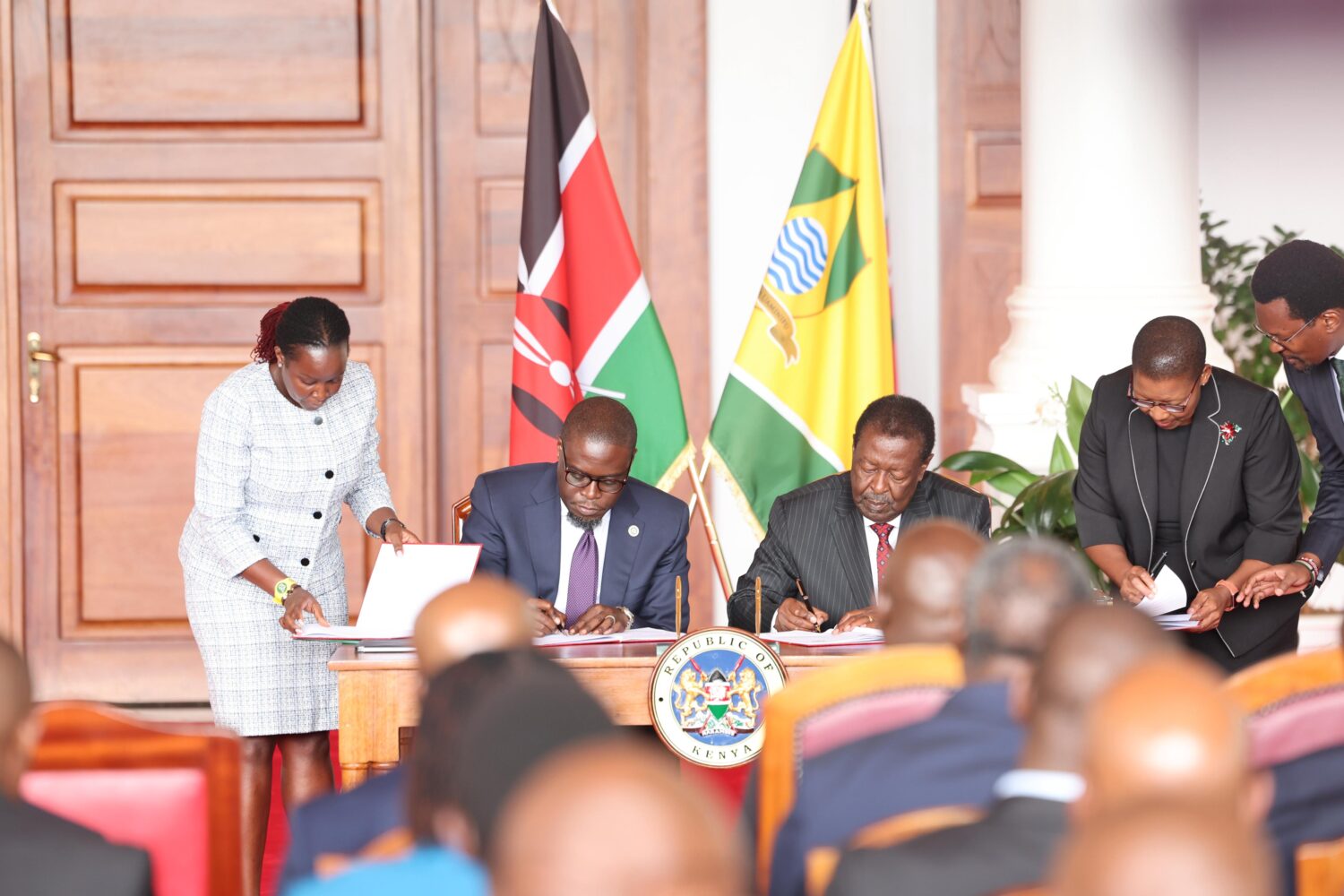

Theophilus Muturi, Managing Director of the Kenya Plant Health Inspectorate Service (KEPHIS), emphasised the role of national leadership.

“It is the responsibility of governments to establish genebanks and the infrastructure needed to store plant genetic resources. We also encourage farmers to develop seed systems or community seed banks where they can store varieties that are critical to them and adapted to different ecological zones,” he said.

Despite the risks, the report identifies opportunities. Fourteen African countries report that 44 percent of their seed collections have been studied and described, exceeding the global average. Meanwhile, 21 countries are actively breeding improved varieties of 81 crop species, including underutilised crops such as African eggplant, amaranth, moringa and indigenous vegetables.

The report calls for urgent, coordinated action to strengthen policies, invest in seed systems and genebanks, build scientific and technical capacity, and support farmers and communities as custodians of plant genetic diversity.

Without decisive action, Africa risks losing irreplaceable resources essential for food security, resilience and sustainable development.