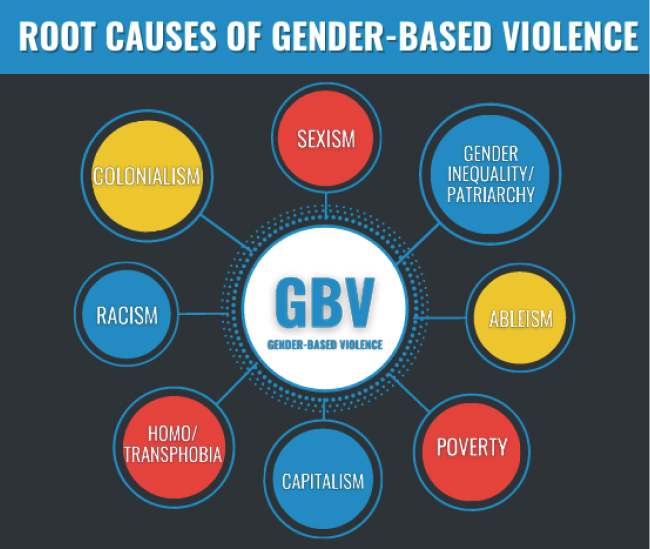

Gender-Based Violence (GBV), including femicide, remains a widespread crisis in Kenya, cutting across urban and rural settings, social classes, and age groups.

While the problem is national, certain geographic, situational, and demographic “hotspots” reveal where risks are most concentrated and why targeted interventions are urgently needed.

According to the report done by the technical working group on gender-based violence, informal urban settlements, overcrowding, poverty, and weak policing create fertile ground for abuse.

In Kakamega County, a key informant described how violence is normalized in public spaces:

“One particularly disturbing manifestation is the public undressing of women in market centres or towns, typically triggered by disapproval of their attire.” Such incidents reflect deeply entrenched gender norms that legitimize punishment and control.

The nature of violence often shifts between rural and urban areas. In Garissa County, a community worker explained, “While fewer rape and defilement incidents are reported in urban Garissa, cases of murder are more common in these areas.”

This contrast highlights how isolation, limited reporting systems, and social dynamics shape different forms of harm.

Coastal counties including Kwale, Kilifi, Mombasa, and Lamu remain hotspots for child sex tourism and trafficking, where poverty intersects with tourism economies.

A resident in Msambweni noted how this combination increases the vulnerability of adolescent girls to exploitation.

Situational risks also intensify violence. In Uasin Gishu, a survivor observed seasonal spikes tied to farming cycles: “When harvest time comes, we witness a lot of physical violence compared to when we are planting.”

Schools and public transport have emerged as risky spaces, with reports of harassment and exploitation by authority figures and service providers.

In Kajiado, a survivor warned, “These boda boda riders sometimes use gifts, money, or favours to coerce or manipulate vulnerable girls into exploitative or abusive relationships.”

Demographic vulnerabilities further shape the crisis. Older women face lethal witchcraft accusations, often linked to land disputes.

A key informant in Kisii County lamented, “We have witnessed lynching of elderly women often under the guise of witchcraft accusations when the motivation is to get hold of their land.”

Women and girls with disabilities, adolescents out of school, and persons with mental health challenges also face heightened risk due to isolation and barriers to reporting.

Emerging trends show violence moving online. Technology-facilitated GBV, including cyberstalking and harassment, increasingly targets women in public life.

As one survivor in Kisumu recalled, “When I reported the incidents… I was told to ‘toughen up’ because it was part of political competition.”

Despite growing activism and reporting, gaps in law enforcement, data systems, and survivor support persist.

As a Mombasa informant summed up, “Femicide may not be clearly defined in our laws, but we know it when we see it.”

Mapping these hotspots underscores a clear message: ending GBV in Kenya requires localized, culturally sensitive, and coordinated responses that address both the roots and realities of violence.