Cervical cancer should not still be taking Kenyan women in their most productive years. Yet it does; quietly, painfully, and often too late.

The tragedy is not only the loss, but also that cervical cancer is one of the most preventable cancers we face.

Kenya is estimated to record about 5,845 new cervical cancer cases and 3,591 deaths in a single year (2023). These are not just statistics, they represent mothers, daughters, colleagues, and friends, and families forced into difficult financial and emotional decisions.

As Cervical Cancer Awareness Month comes to an end, the key take away is clear. We must move from awareness to action.

The virus behind cervical cancer, and the breakthrough that changed prevention.

Nearly all cervical cancer is caused by persistent infection with high-risk strains of the human papillomavirus (HPV). HPV is common, the immune system clears most infections, but when high-risk HPV persists, it can cause changes in the cervix that may develop into cancer over time.

The HPV vaccine was a scientific breakthrough because it prevents the infection that starts the pathway to cancer. In plain terms, the vaccine “teaches” the immune system to recognise HPV early and block it, before it can settle and do long-term harm.

HPV is also linked to other cancers (including cancers of the mouth/throat, anus, vulva, vagina and penis). So, vaccination is not only about protecting girls, but also about protecting communities.

Sometimes Kenyans ask: Does it really work?

Globally, the evidence is no longer theoretical. Countries that introduced HPV vaccination earlier are already seeing major reductions in severe cervical disease and cervical cancer.

A large national study in England reported substantial reductions in cervical cancer following HPV vaccination, with benefits seen across socioeconomic groups. This matters because it confirms the most important point: HPV vaccination prevents cancer.

Kenya introduced HPV vaccination into routine immunisation in 2019. But in a major step forward, Kenya transitioned to a single-dose HPV vaccination schedule in November 2025, following global evidence reviewed by WHO’s immunisation experts.

This shift is not a small administrative change, it is a practical life-saving advantage.

One dose means fewer missed second appointments, fewer transport challenges, less disruption for parents, and simpler delivery through schools and facilities. In public health, the easiest programme is often the most effective programme.

This is why the move to a single dose HPV vaccine matter. It is also why action is needed now.

For parents and guardians of girls aged 10 to 14, this is a critical window. Kenya’s HPV programme prioritises early adolescence because the vaccine offers the strongest protection before exposure to the virus. If your daughter is in this age group, HPV vaccination should be treated like any other essential childhood vaccine. It is not a future issue. It is a protection decision made today.

Vaccination alone is not enough. Screening still matters for women. While vaccination protects the next generation, screening protects women now. This is why the World Health Organization’s cervical cancer elimination strategy rests on three pillars: ninety percent of girls fully vaccinated by age fifteen, seventy percent of women screened by age thirty-five and again by forty-five and ninety percent of those with disease treated.

Cervical cancer often develops silently in its early stages. Screening ensures the disease is detected early, when treatment is most effective and lives can be saved.

If the solution is this powerful, why is uptake still not universal? Because misinformation spreads fast, fear is real, and access is uneven. The facts are clear. HPV vaccines are widely used around the world and are safe and effective. The greatest risk is not vaccination. It is delay. Delay in vaccinating girls, screening women or treating pre-cancer.

Insurers, employers, and leaders have a critical role to play. Prevention must be the easiest choice. Too often, we act only when disease is advanced and expensive. Cervical cancer elimination requires the opposite approach. We must invest early.

The insurance sector and employers can accelerate progress by reducing friction. Screening and precancer treatment should be covered with clear and simple access. Reminders through SMS or WhatsApp can normalise screening.

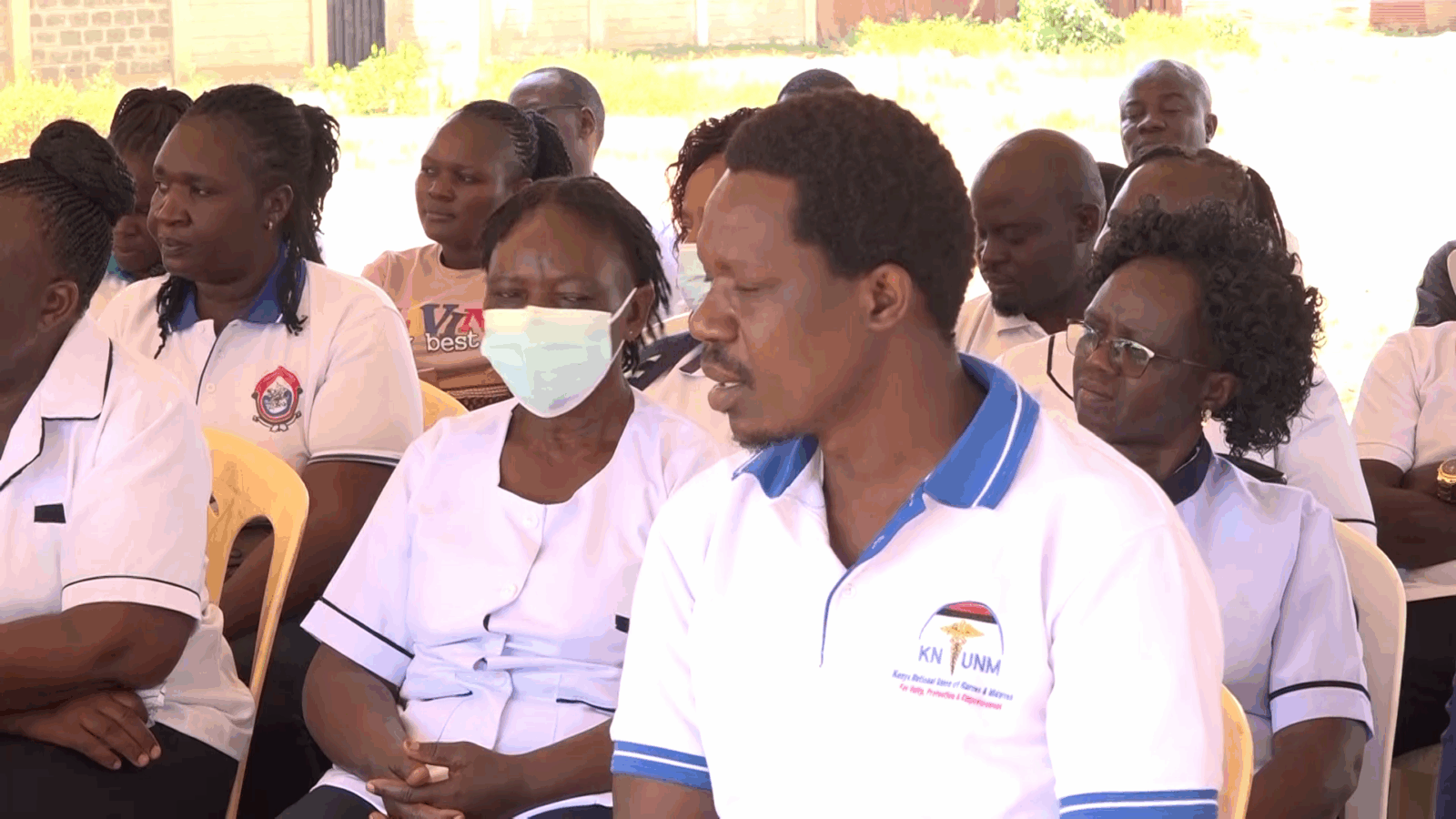

School based and workplace health days can link vaccination, screening, and referrals. Partnerships with counties and healthcare providers can bring services closer to communities.

Prevention is compassionate. It is also economically sound. It protects families from catastrophic health costs and protects health systems from avoidable long-term strain.

Cervical cancer elimination is achievable within a generation if we do the basics consistently. Vaccinate girls. Screen women. Treat disease early.

This January, action matters. Parents can protect their daughters early. Women can screen on time. Leaders in business, faith, education, and health can make prevention easier and normal.

One dose can change a life. One generation can change a country.

By Dr Musa Misiani, Chief Operating Officer, Jubilee Health Insurance