Co- founder Ufanisi Research Network, Juliet Oluoch, has analyzed the significant implications of the United States government’s formal withdrawal from the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), the foundational international treaty adopted in 1992 to coordinate global climate response.

This treaty supports major climate processes including the Paris Agreement and annual COP negotiations.

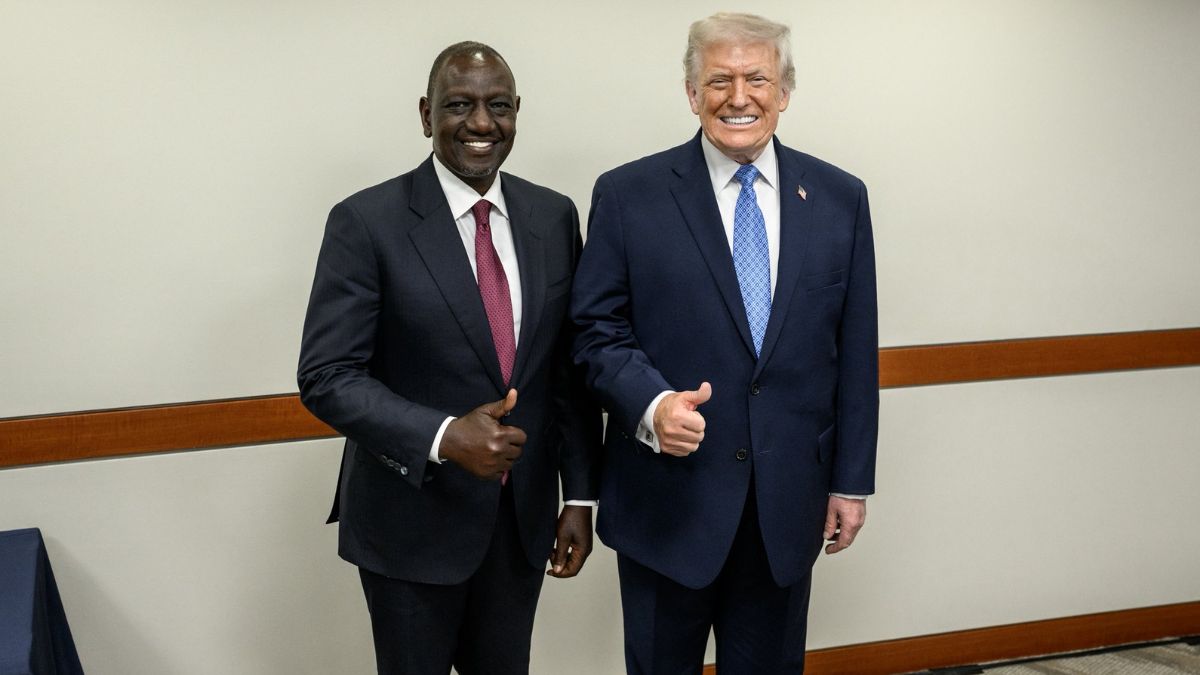

The US administration cites three main rationales for the withdrawal, that is, prioritizing national interests and sovereignty, arguing that multilateral climate institutions are misaligned with American economic priorities; redirecting taxpayer funds toward areas where the US can exert more direct influence rather than complex multilateral structures; and advancing the America First agenda, which is skeptical of multilateral governance, questions climate science, and favors fossil fuel development and energy independence.

For Kenya, the withdrawal has profound implications across three major areas.

In terms of diplomatic and strategic relations, the move weakens Kenya’s ability to build strategic coalitions with one of the world’s largest historic emitters and advocate for loss and damage finance, adaptation support, and technology transfer through key platforms.

Regarding climate finance and technical support, Kenya relies heavily on climate finance for adaptation and development initiatives, including renewable energy and resilience building.

US contributions have historically supported mechanisms like the Green Climate Fund.

The withdrawal stops these funding streams, creating uncertainty for projects scaling geothermal, wind, and solar infrastructure.

Technical cooperation programs training Kenyan scientists and policy experts may be scaled down or lost, weakening local capacity and slowing progress toward Kenya’s Nationally Determined Contributions.

On the economic front, climate policy uncertainty in the US will ripple globally, affecting investor confidence in clean energy markets.

Kenya’s green investment landscape, which has benefited from multinational participation catalyzed by US engagement, risks slower private sector investment and higher capital costs for green projects.

Globally, the withdrawal will weaken collective climate response, as achieving consensus on ambitious mitigation commitments becomes harder.

Other nations may feel less pressure to uphold their commitments, risking a downward spiral in global climate ambition.

Leadership dynamics will shift, with the European Union, China, and emerging economies potentially filling the vacuum, reshaping global climate governance in ways that may not align with developing countries’ priorities, particularly regarding loss and damage finance and equitable adaptation resources.

The withdrawal also deepens the trust deficit for developing nations that contribute least to climate change yet face the greatest impacts, potentially making future negotiations and shared financing commitments more contentious.

Juliet emphasized that Kenya’s path forward requires strengthened South-South cooperation, diversified climate finance partnerships beyond donor funding, and increased regional leadership in African climate diplomacy.

The African Union must now step up to develop alternative climate finance strategies and investments to navigate this major geopolitical shift in global climate action.