Mercy Chege was a healthy baby, with healthy eyes and an excellent eyesight. But things started going south when she turned four. She started developing uncomfortable itchiness in her eyes.

Her loving parents could not sit pretty as their beloved daughter was hurting. And so, they took her to PCEA Kikuyu Hospital, where doctors diagnosed her with an allergy of the eyes.

Mercy would battle constant “allergies of the eyes” for years, and when she was in Class Four, an ophthalmologist recommended that she starts using glasses.

Yet all these efforts were all in vain.

Upon reaching Class Six, Mercy’s eyes took a turn for the worse. Slowly but surely, she started having blurry visions.

In an interview with TV47, Mercy narrated how at this point her life changed— she started seeing merged letters, roads became dangerous, her independence slipped away quietly. Once a confident and self-reliant Mercy found herself counting steps, depending on voices, memorising spaces. Simple tasks like reading a message, crossing the street, recognising a friend became daily obstacles. Dignity, she said, is often the first thing blindness takes.

She was advised to start using contact lenses. But even the contact lenses felt like a quick fix. What was a permanent solution to Mercy’s eyesight predicarments?

Cornea transplant

Fast forward… Mercy is in Form Two, but he eyes were becoming worse. It is a this point that she opted to try and find remedy in different hospital.

At Lions SighFirst Eye Hospital, the ophthalmologist delivered a shocker! Cornea transplant.

At the time, the concept of cornea transplant was very foreign not just to Mercy but her parents too.

According to Cleveland Clinic, a cornea transplant — also called corneal grafting — involves replacing damaged or diseased corneal tissue with a healthy donor cornea.

More often, cornea transplant replaces a damaged cornea with tissue from a deceased donor, and that is why the concept is foreign t, not just Kenyans, but Africans.

In many African cultures, death is sacred. The body is prepared carefully, preserved whole, untouched, returned to the earth as it came. To interfere with and/or disturb the body of the deceased, elders warn, will attract the wrath of his or her spirits.

For this reason, general organ donation remains a deeply uncomfortable subject for many African families, often avoided in moments already heavy with grief.

Fortunately for Mercy, an open-minded family in grief offered to donate a cornea for her. The noble family would never meet Mercy, neither will they witness the impact of their choice, but their generosity travelled quietly—from death to life.

This reporter was granted exclsuve access to witness a procedure many Kenyans have never seen.

Witnessing the 45-minute procedure

The theatre is silent when Mercy Chege closes her eyes. It is not fear that stills her, but hope, the fragile kind that has been missing for years. Above her, surgical lights burn bright, flooding the room with white intensity. Around her, gloved hands move with quiet purpose, rehearsed and precise. Somewhere beyond the sterile hospital walls, a family is mourning a loved one they will never see again.

Preparations begin with the surgeons examining the donated cornea carefully, checking for viability. Mercy’s eye is numbed and stabilised. Before the first incision, the room pauses—a brief prayer is said, in a classic example where faith and science share the same space.

Then the surgeon begins. With microscopic precision, the damaged cornea is measured, marked and gently removed. The donated tissue kept hydrated and protected is placed into position. Sixteen tiny stitches secure it in place. Less than forty-five minutes later, the work is done.

A new window to the world has been fitted.

Challenges facing cornea transplant

Hospitals have trained surgeons, modern theatres and eye banks. What they often do not have is consent. Many families refuse donation, guided by fear, cultural taboos, or misunderstanding. Some believe cutting the dead disturbs the spirit. Others mistrust the medical system, worried about misuse or disrespect.

Behind such moments is the unseen work of eye banks. Cornea retrieval must happen within six hours after death. Tissue is screened, tested, and preserved under strict medical protocols, blood tests are conducted, cell counts analysed.

Every step is careful, regulated, and respectful. Yet with low local donation rates, Kenya relies heavily on imported corneas—an option that is expensive, limited, and unable to meet growing demand.

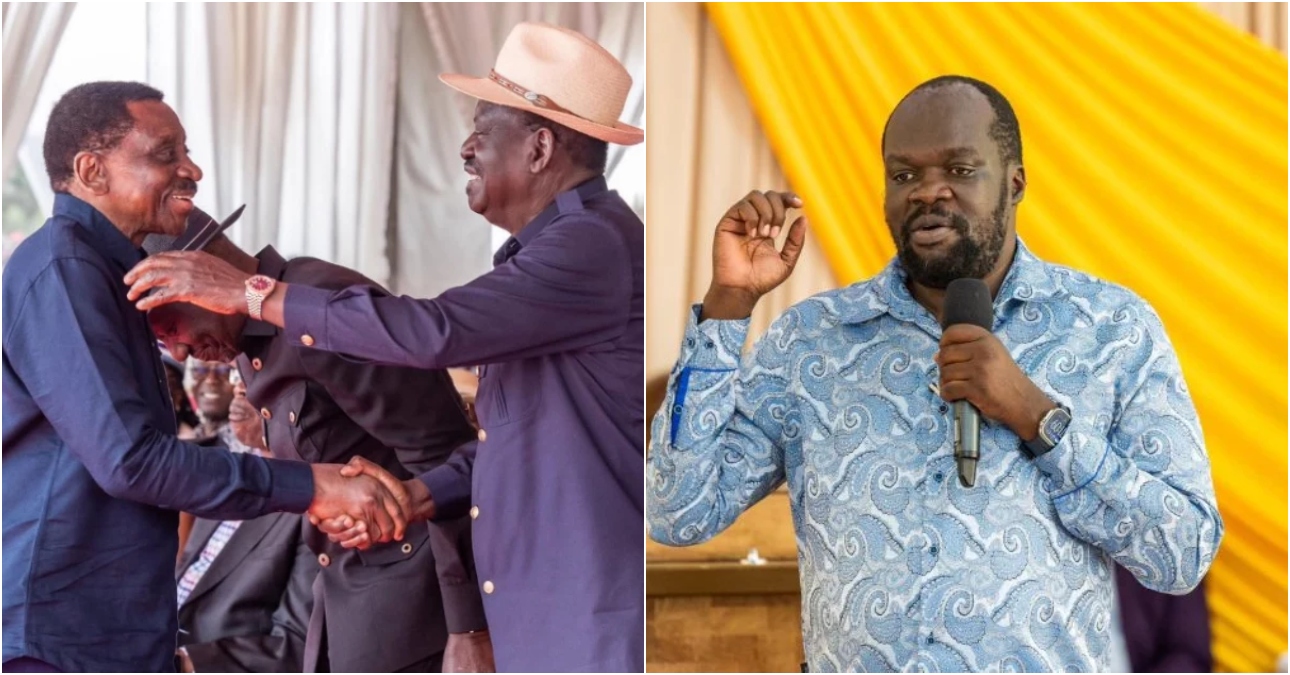

Stephen K. Cheruiyot understands this miracle personally. Before receiving a cornea transplant, the MCA for Kapchemutwa Ward in Elgeyo Marakwet County carried out public duties seeing only shadows and blurred outlines. Today, his restored sight allows him to serve fully and to speak openly about the gift that changed his life.

Faith leaders, too, are beginning to speak. Across religions, the message is becoming clearer: restoring sight is not a violation of belief, but an act of mercy.

Health officials say the real challenge is not medicine, but conversation. Many Kenyans remain unaware of donor rights, safeguards, or the fact that cornea donation does not delay burial or alter funeral rites. Kenya does not lack ability. It lacks awareness.

When Mercy wakes, her eye is covered. Healing will take time. Vision will return slowly, not instantly. But something has already changed. Darkness no longer feels permanent.